| ||||

| Add caption |

Bear with me, this

will be about writing soon enough. But I

start with the somewhat iconic words of the great Panamanian boxer, Roberto

Duran, when he walked out in the eighth round of the second Ray Leonard

fight. I loved Duran and it broke my

heart when he quit. Leonard was too

quick, too elusive that night and Duran just couldn’t catch him. Frustration.

When do you walk

away? Boxers often don’t know, that’s

for sure. Every climber whoever died in

the mountains probably ought to have walked away earlier, that’s also for sure. And writers? That can be a pretty tough call,

too. Elmore Leonard thought he was writing

his last book, until yesterday when he was awarded a medal for Distinguished Contribution

to American Letters. He said the award “energized

him” and that he would write on. Leonard

is 87.

Last week Philip Roth

announced that he wouldn’t write anymore.

This can hardly be considered a loss: he’s written more books already

than almost anyone has read. It would be

highly doubtful to imagine that his best work would have been ahead of him:

he’s almost eighty, with thirty books to his name. When we need him, he’ll still be there in his

thirty books. I think I have only read

four of them.

So, I’m not disturbed

by that announcement. But I do find his

“advice” to Julian Tepper disheartening:

http://tpr.ly/X3XGcH

Disheartening

because, well, it suggests that Roth would wish away those thirty books, wish

away the life he’s led. And that’s more

than disheartening, it’s heartbreaking.

And good for Tepper.

I’m buying his book immediately based on his reaction.

But the heart of this

message is yet another public announcement of retirement from the writing life,

by the British writer and climber, Andy Kirkpatrick:

Andy is a very very good writer. Andy has two very fine books, Psychovertical

and Cold Wars, to his name, and it’s very sad to think that there may not be

any more.

His books have won awards, justifiably, including our own

little world’s most prestigious, The Boardman-Tasker. And he has been terrific promoter of

them. I saw him at the Banff Mountain

Book Awards in 2006. His performance there was

absolutely the best public performance by a writer I have ever seen in my

entire life. And I see a lot of such

“performances,” including a few by Nobel Prize wining writers. Kirkpatrick was the best.

So, I hate to see him “throw the teddy out of the pram.”

But the bottom line is this: Making a full time living from

writing, and writing (itself) are two very very different animals.

You can write, and you can make it important in your life,

even central. But making a living at it,

and it alone? My friends, buy a lottery ticket, play the horses, go to Vegas:

you’ll get better odds.

One problem Andy alludes to, but I’m not sure the degree to

which it has sunk in, is that when he started out he wrote to support his

climbing. But the scales tipped and at some point he began climbing to support

his writing. This can be a very dicey

predicament in which to find yourself.

His early climbs were already sufferfests. Where do you go from there? You up the ante, you up the ante, and pretty

soon there’s nowhere to go but the cemetery in Chamonix or the crevasse on Denali. Dead men tell no tales.

Look at the graceful writing career of David Roberts, who

gave us at least two of the best American books on climbing: Mountain of My

Fear and Deborah; his memoir, On the Ridge Between Life and Death is a third

great book. He kept writing long after

his career of climbing at the bloody edge of the possible ended. He became a kind of historian of exploration

history. He became a writer. It looks like a great life, but don’t forget

that the books don’t write themselves.

I know Andy is severely dyslexic and that he hammered those

books out at a high price. But I don’t

know anyone whose books came easy. Who

is to say that there are not many ways to pay the high price of getting a book

out into the world? Time is the least of

it.

Ray Carver used to give all of his students grades of

A. He said something like, who am I to

discourage someone who may have a great masterpiece within them? He encouraged every one of his students to try

to find that masterpiece; or well, at least he didn’t discourage them.

Find your “day job,” Andy, but that doesn’t have to be

mutually exclusive to the writing life. Ours will be dimmer future without another of your books in it.

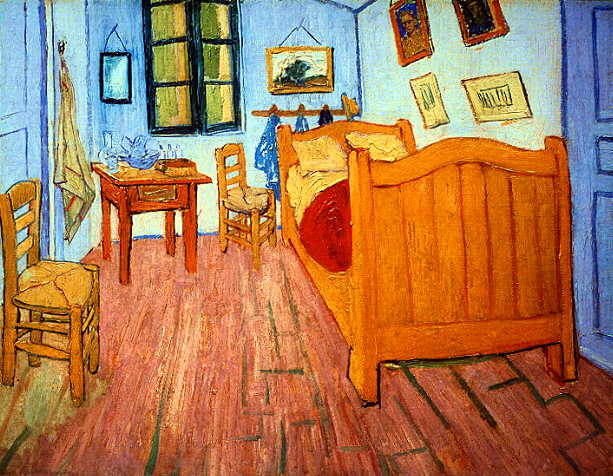

“In spite of everything I shall rise again: I will take up

my pencil, which I have forsaken in my great discouragement, and I will go on

drawing.”—Vincent van Gogh.

Pick up those pencils, friends!